Be skeptical of the advice of successful people, they suffer from deep survivor bias. Hundreds of other people did exactly what they did and failed. Chances are their success has more to do with luck than the advice they are given you.

I guess Monkey Island turns 25 this month. It’s hard to tell.

Unlike today, you didn’t push a button and unleash your game to billions of people. It was a slow process of sending “gold master” floppies off to manufacturing, which was often overseas, then waiting for them to be shipped to stores and the first of the teaming masses to buy the game.

Of course, when that happened, you rarely heard about it. There was no Internet for players to jump onto and talk about the game.

There was CompuServe and Prodigy, but those catered to a very small group of very highly technical people.

Lucasfilm’s process for finalizing and shipping a game consisted of madly testing for several months while we fixed bugs, then 2 weeks before we were to send off the gold masters, the game would go into “lockdown testing”. If any bug was found, there was a discussion with the team and management about if it was worth fixing. “Worth Fixing” consisted of a lot of factors, including how difficult it was to fix and if the fix would likely introduce more bugs.

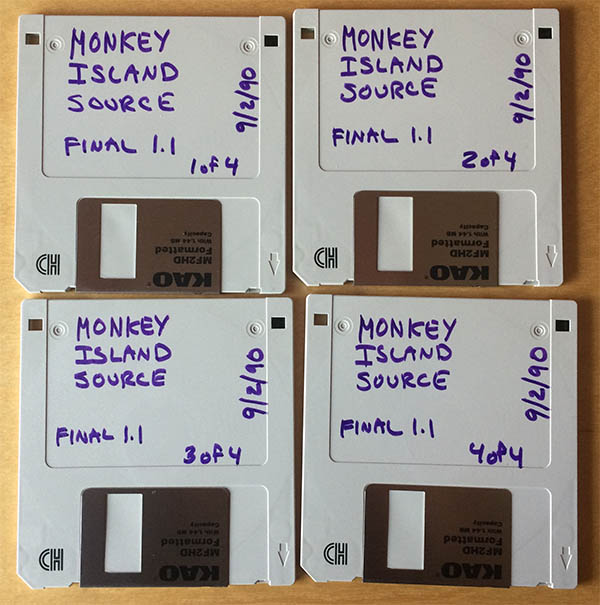

Also keep in mind that when I made a new build, I didn’t just copy it to the network and let the testers at it, it had to be copied to four or five sets of floppy disk so it could be installed on each tester’s machine. It was a time consuming and dangerous process. It was not uncommon for problems to creep up when I made the masters and have to start the whole process again. It could take several hours to make a new set of five testing disks.

It’s why we didn’t take getting bumped from test lightly.

During the 2nd week of “lockdown testing”, if a bug was found we had to bump the release date. We required that each game had one full week of testing on the build that was going to be released. Bugs found during this last week had to be crazy bad to fix.

When the release candidate passed testing, it would be sent off to manufacturing. Sometimes this was a crazy process. The builds destined for Europe were going to be duplicated in Europe and we needed to get the gold master over there, and if anything slipped there wasn’t enough time to mail them. So, we’d drive down to the airport and find a flight headed to London, go to the gate and ask a passenger if they would mind carry the floppy disks for us and someone would meet them at the gate.

Can you imagine doing that these days? You can’t even get to the gate, let alone find a person that would take a strange package on a flight for you. Different world.

After the gold masters were made, I’d archive all the source code. There was no version control back then, or even network storage, so archiving the source meant copying it to a set of floppy disks.

I made these disk on Sept 2nd, 1990 so the gold masters were sent off within a few days of that. They have a 1.1 version due to Monkey Island being bumped from testing. I don’t remember if it was in the 1st or 2nd week of “lockdown”.

It hard to know when it first appeared in stores. It could have been late September or even October and happened without fanfare. The gold masters were made on the 2nd, so that what I’m calling The Secret of Monkey Island’s birthday.

Twenty Five years. That’s a long time.

It amazes me that people still play and love Monkey Island. I never would have believed it back then.

It’s hard for me to understand what Monkey Island means to people. I am always asked why I think it’s been such an enduring and important game. My answer is always “I have no idea.”

I really don’t.

I was very fortunate to have an incredible team. From Dave and Tim to Steve Purcell, Mark Ferrari, an amazing testing department and everyone else who touched the game’s creation. And also a company management structure that knew to leave creative people alone and let them build great things.

Monkey Island was never a big hit. It sold well, but not nearly as well and anything Sierra released. I started working on Monkey Island II about a month after Monkey Island I went to manufacturing with no idea if the first game was going to do well or completely bomb. I think that was part of my strategy: start working on it before anyone could say “it’s not worth it, let’s go make Star Wars games”.

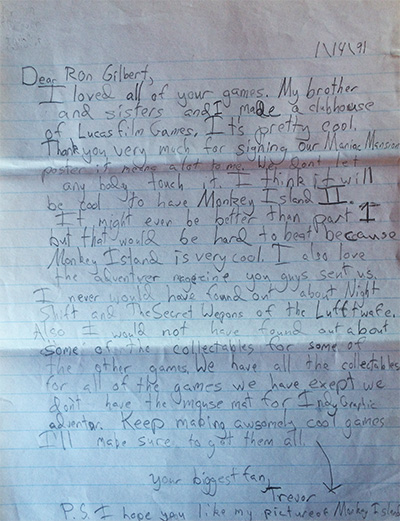

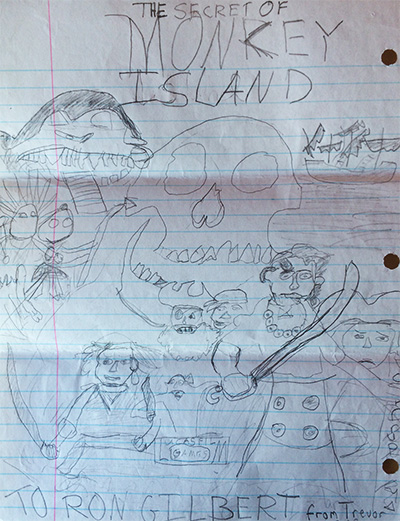

There are two things in my career that I’m most proud of. Monkey Island is one of them and Humongous Entertainment is the other. They have both touched and influenced a lot of people. People will tell me that they learned english or how to read from playing Monkey Island. People have had Monkey Island weddings. Two people have asked me if it was OK to name their new child Guybrush. One person told me that he and his father fought and never got along, except for when they played Monkey Island together.

It makes me extremely proud and is very humbling.

I don’t know if I will ever get to make another Monkey Island. I always envisioned the game as a trilogy and I really hope I do, but I don’t know if it will ever happen. Monkey Island is now owned by Disney and they haven’t shown any desire to sell me the IP. I don’t know if I could make Monkey Island 3a without complete control over what I was making and the only way to do that is to own it. Disney: Call me.

Maybe someday. Please don’t suggest I do a Kickstarter to get the money, that’s not possible without Disney first agreeing to sell it and they haven’t done that.

Anyway…

Happy Birthday to Monkey Island and a huge thanks to everyone who helped make it great and to everyone who kept it alive for Twenty Five years.

I thought I’d celebrate the occasion by making another point & click adventure, with verbs.

If you’re wondering why it’s so quiet over here at Grumpy Gamer, rest assured, it has nothing to do with me not being grumpy anymore.

The mystery can be solved by heading on over to the Thimbleweed Park Dev Blog and following fun antics of making a game.

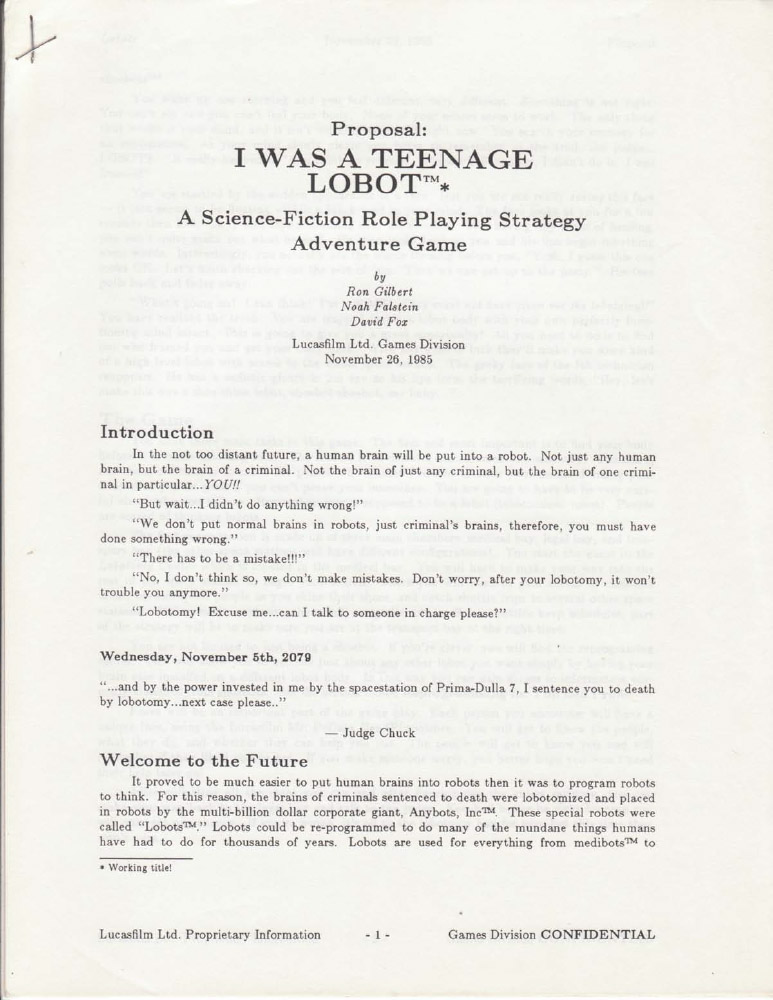

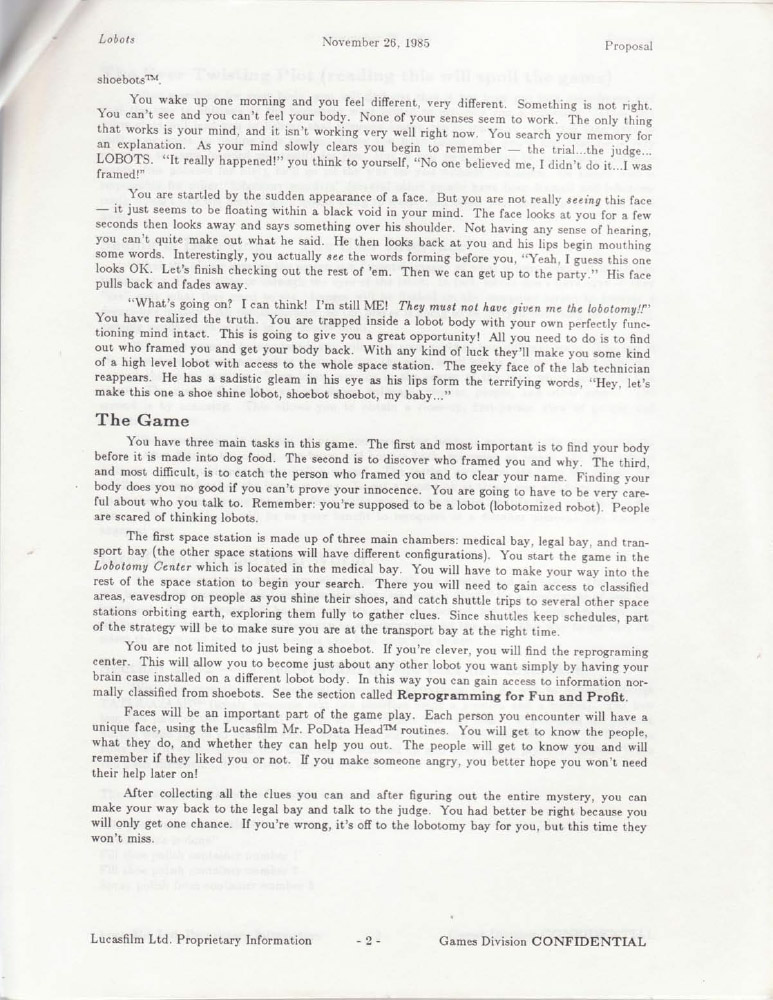

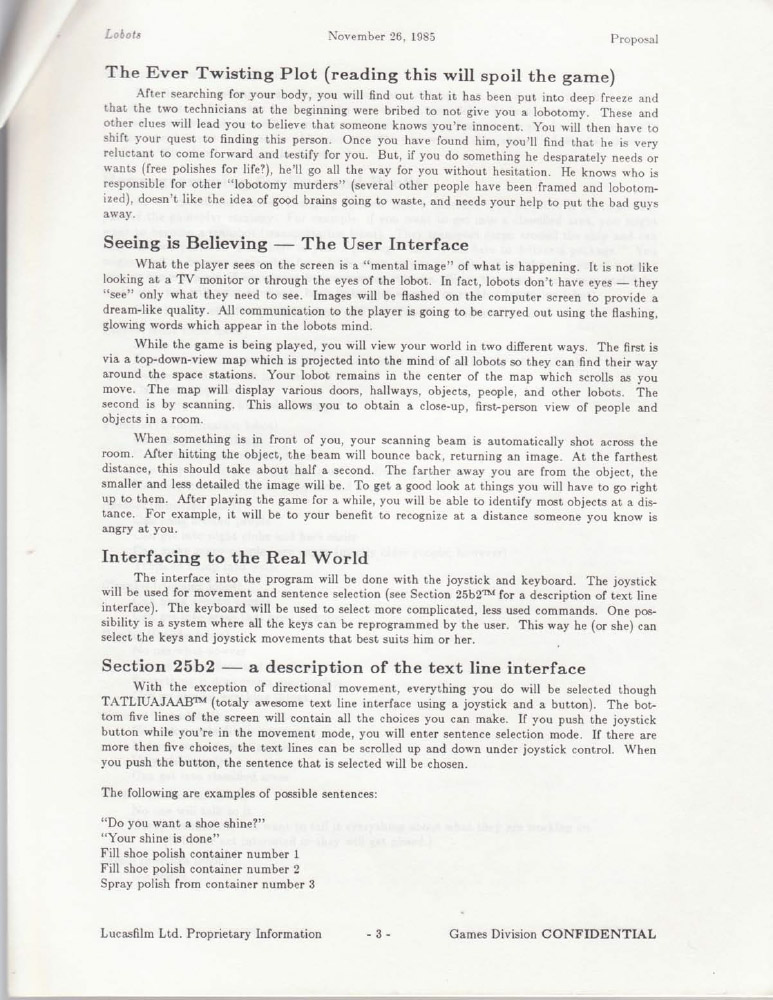

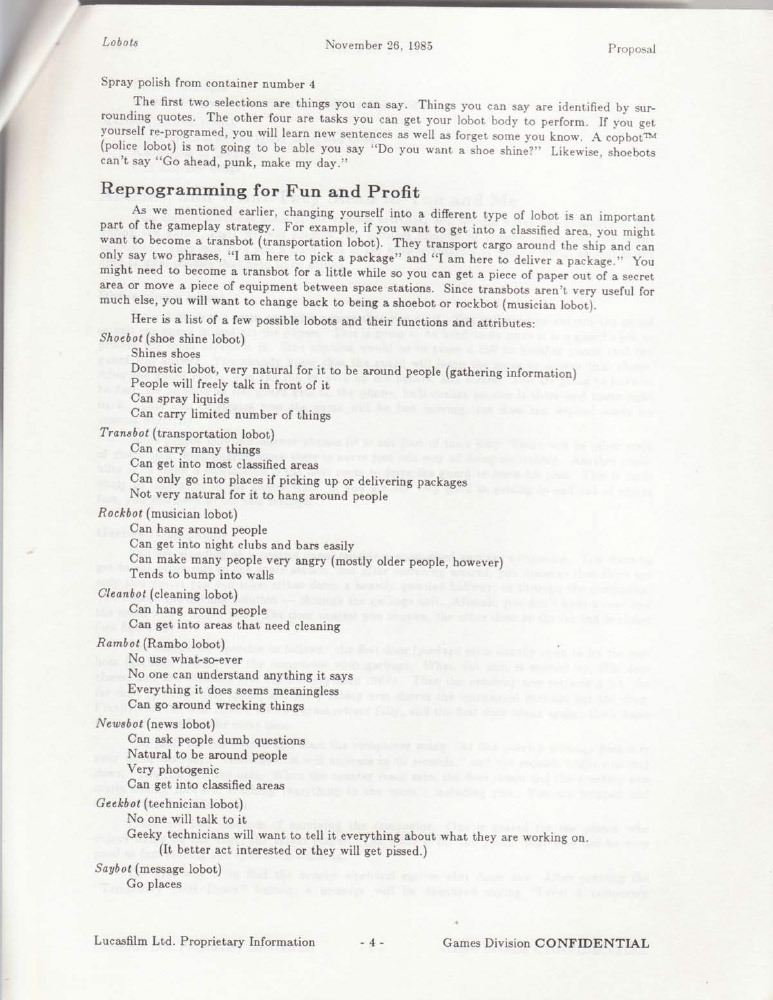

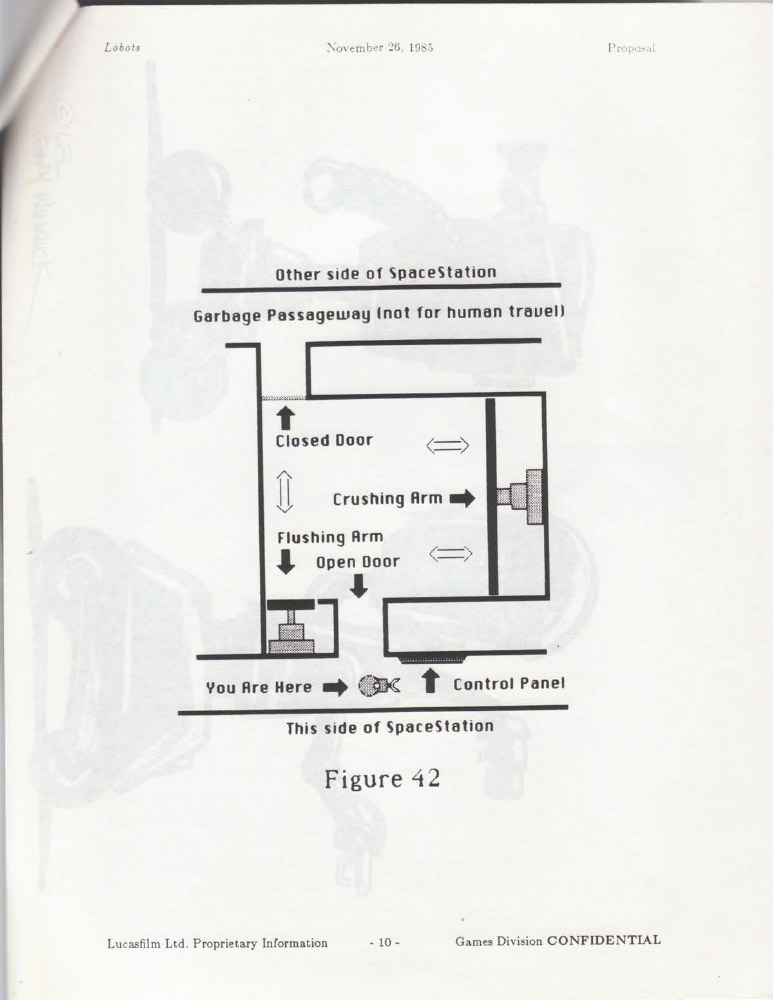

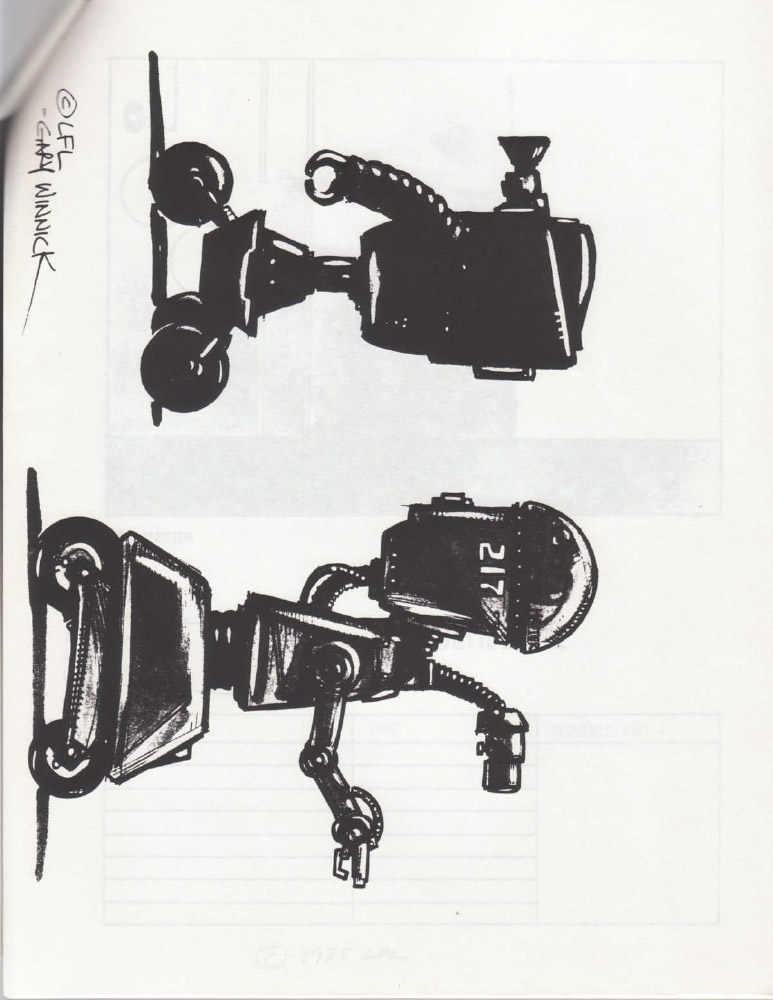

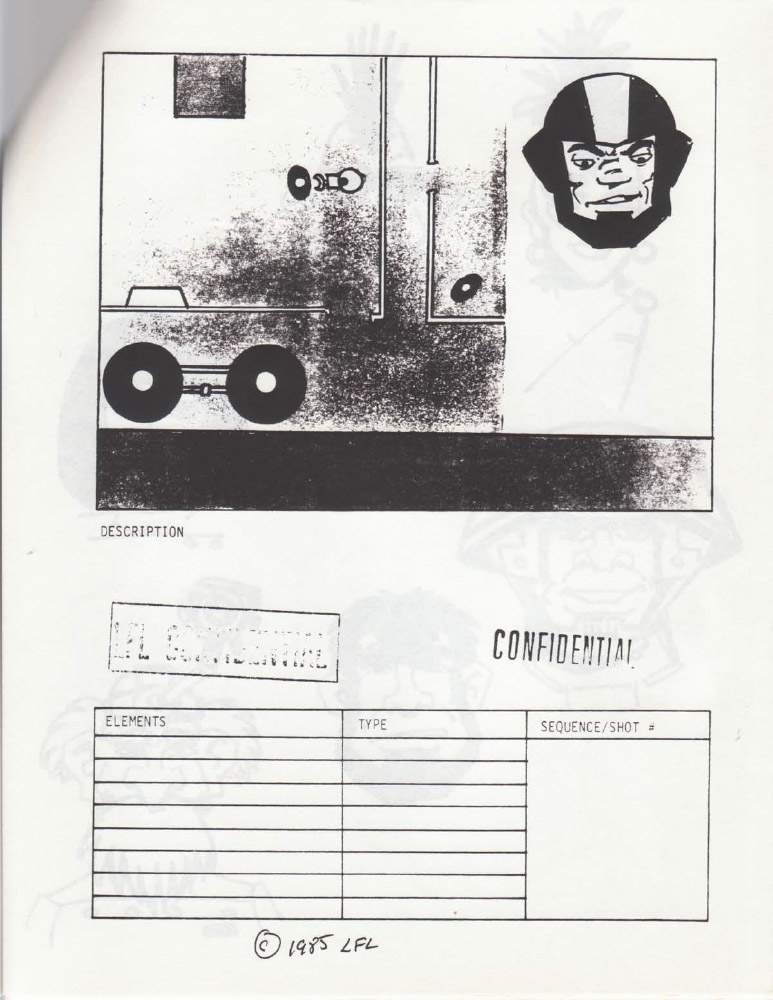

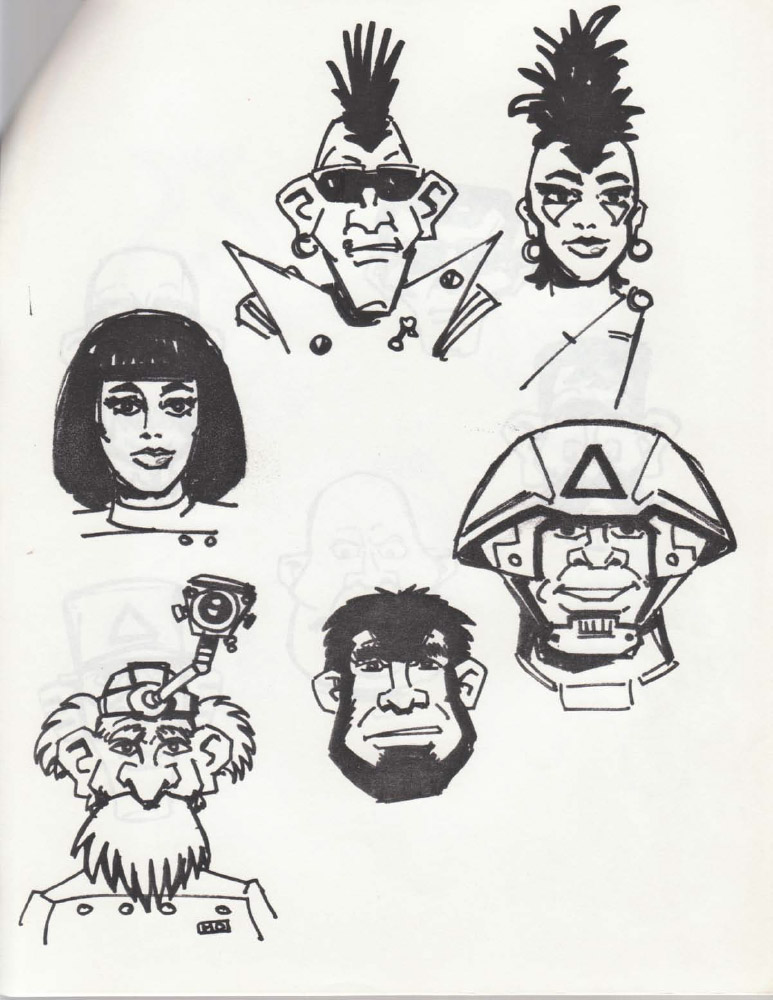

This was the first design document I worked on while at Lucasfilm Games. It was just after Koronis Rift finished and I was really hoping I wouldn’t get laid off. When I first joined Lucasfilm, I was a contractor, not an employee. I don’t remember why that was, but I wanted to get hired on full time. I guess I figured I’d show how indispensable I was by helping to churn out game design gold like this.

This is probably one of the first appearances of “Chuck”, who would go on to “Chuck the Plant” fame.

You’ll also notice the abundance of TM’s all over the doc. That joke never gets old. Right?

Many thanks to Aric Wilmunder for saving this document.

Shameless plug to visit the Thimbleweed Park Development Diary.

The C64 version of Maniac Mansion didn’t use a mouse, it used one of these:

A year later we did the IBM PC version and it had keyboard support for moving the cursor because most PCs didn’t have a mouse. Monkey Island also had cursor key support because not everyone had a mouse.

Use the above facts to impress people at cocktail parties.

Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah.

Blah Blah Blah Blah, Blah Blah Blah, Blah Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah Blah Blah, Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah!!!

Blah, Blah Blah Blah Blah, Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah, Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah? Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah.

Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah, Blah Blah Blah Blah, Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah, Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah, Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah Blah Blah?

Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah Blah. Blah Blah Blah!

Blah.

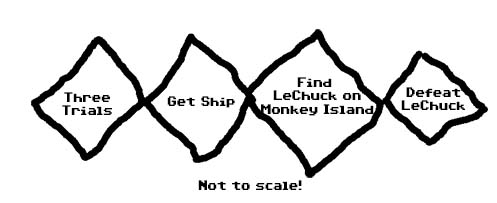

In part 1 of 1 in my series of articles on games design, let’s delve into one of the (if not THE) most useful tool for designing adventure games: The Puzzle Dependency Chart. Don’t confuse it with a flow chart, it’s not a flow chart and the subtle distinctions will hopefully become clear, for they are the key to it’s usefulness and raw pulsing design power.

There is some dispute in Lucasfilm Games circles over whether they were called Puzzle Dependency Charts or Puzzle Dependency Graphs, and on any given day I’ll swear with complete conviction that is was Chart, then the next day swear with complete conviction that it was Graph. For this article, I’m going to go with Chart. It’s Sunday.

Gary and I didn’t have Puzzle Dependency Charts for Maniac Mansion, and in a lot of ways it really shows. The game is full of dead end puzzles and the flow is uneven and gets bottlenecked too much.

Puzzle Dependency Charts would have solve most of these problems. I can’t remember when I first came up with the concept, it was probably right before or during the development of The Last Crusade adventure game and both David Fox and Noah Falstein contributed heavy to what they would become. They reached their full potential during Monkey Island where I relied on them for every aspect of the puzzle design.

A Puzzle Dependency Chart is a list of all the puzzles and steps for solving a puzzle in an adventure game. They are presented in the form of a Graph with each node connecting to the puzzle or puzzle steps that are need to get there. They do not generally include story beats unless they are critical to solving a puzzle.

Let’s build one!

I always work backwards when designing an adventure game, not from the very end of the game, but from the end of puzzle chains. I usually start with “The player needs to get into the basement”, not “Where should I hide a key to get into some place I haven’t figured out yet.”

I also like to work from left to right, other people like going top to bottom. My rational for left to right is I like to put them up on my office wall, wrapping the room with the game design.

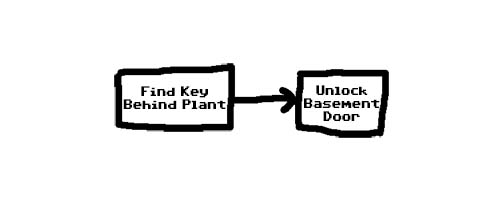

So… first, we’ll need figure out what you need to get into the basement…

And we then draw a line connecting the two, showing the dependency. “Unlocking the door” is dependent on “Finding the Key”. Again, it’s not flow, it’s dependency.

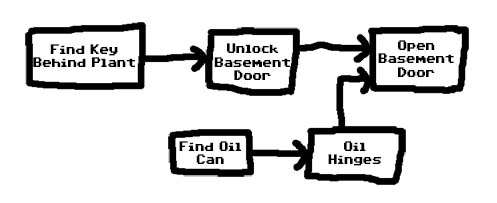

Now let’s add a new step to the puzzle called “Oil Hinges” on the door and it can happen in parallel to the “Finding the Key” puzzle…

We add two new puzzle nodes, one for the action “Oil Hinges” and it’s dependency “Find Oil Can”. “Unlocking” the door is not dependent on “Oiling” the hinges, so there is no connection. They do connect into “Opening” the basement door since they both need to be done.

At this point, the chart is starting to get interesting and is showing us something important: The non-linearity of the design. There are two puzzles the player can be working on while trying to get the basement door open.

There is nothing (NOTHING!) worse than linear adventure games and these charts are a quick visual way to see where the design gets too linear or too unwieldy with choice (also bad).

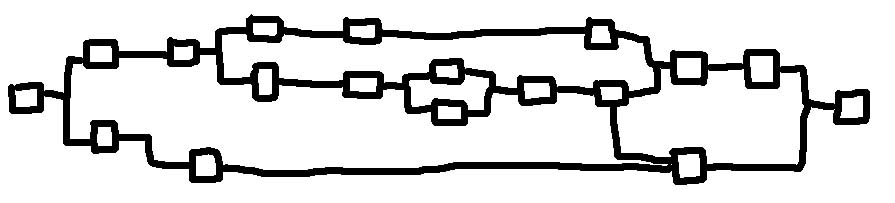

Let’s build it back a little more…

When you step back and look at a finished Puzzle Dependency Chart, you should this kind of overall pattern with a lot of little sub-diamond shaped expansion and contraction of puzzles. Solving one puzzle should open up 2 or 3 new ones, and then those collapses down (but not necessarily at the same rate) to a single solution that then opens up more non-linear puzzles.

The game starts out with a simple choice, then the puzzles begin to expand out with more and more for the player to be doing in parallel, then collapse back in.

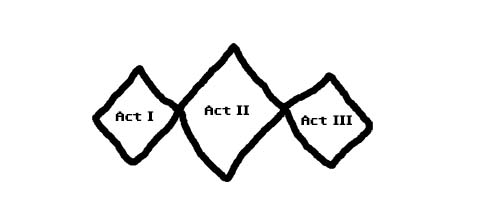

I tend to design adventures games in “acts”, where each act ends with a bottle neck to the next act. I like doing this because it gives players a sense of completion, and they can also file a bunch of knowledge away and (if need) the inventory can be culled).

Monkey Island would have looked something like this…

I don’t have the Puzzle Dependency Chart for Monkey Island, or I’d post it. I’ve seen some online, but they are more “flowcharts” and not “dependency charts”. I’ve had countless arguments with people over the differences and how dependency charts are not flowcharts, bla bla bla. They’re not. I don’t completely know why, but they are different.

Flowcharts are great if you’re trying to solve a game, dependency charts are great if you’re trying to design a game. That’s the best I can come up with.

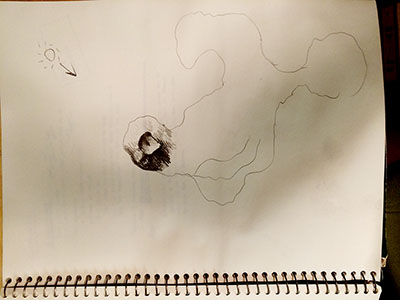

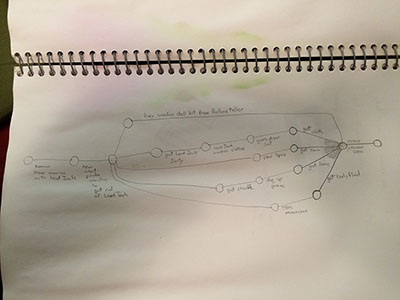

Here is a page from my MI design notebook that shows a puzzle in the process of being created using Puzzle Dependency Charts. It’s the only way I know how to design an adventure game. I’d be lost without them.

So, how do you make these charts?

You’ll need some software that automatically rebuilds the charts as you connect nodes. If you try and make these using a flowchart program, you’ll spend forever reordering the boxes and making sure lines don’t cross. It’s a frustrating and time consuming process and it gets in the way of using these as a quick tool for design.

Back at Lucasfilm Games, we used some software meant for project scheduling. I don’t remember the name of it, and I’m sure it’s long gone.

I’ve only modern program that does this well is OmniGraffle, but it only runs on the Mac. I’m sure there are others, but since OmniGraffle does exactly what I need, I haven’t look much deeper. I’m sure there are others.

OmniGraffle is built on top of the unix tool called graphviz. Graphviz is great, but you have to feed everything in as a text file. It’s a nerd level 8 program, but it’s what I used for DeathSpank.

You can take a look at the DeathSpank Puzzle Dependency Chart here, but I warn you, it’s a big image, so get ready to zoom-n-scroll™.

Hopefully this was interesting. I could spend all day long talking about Puzzle Dependency Charts. Yea, I’m a lot of fun on a first date.

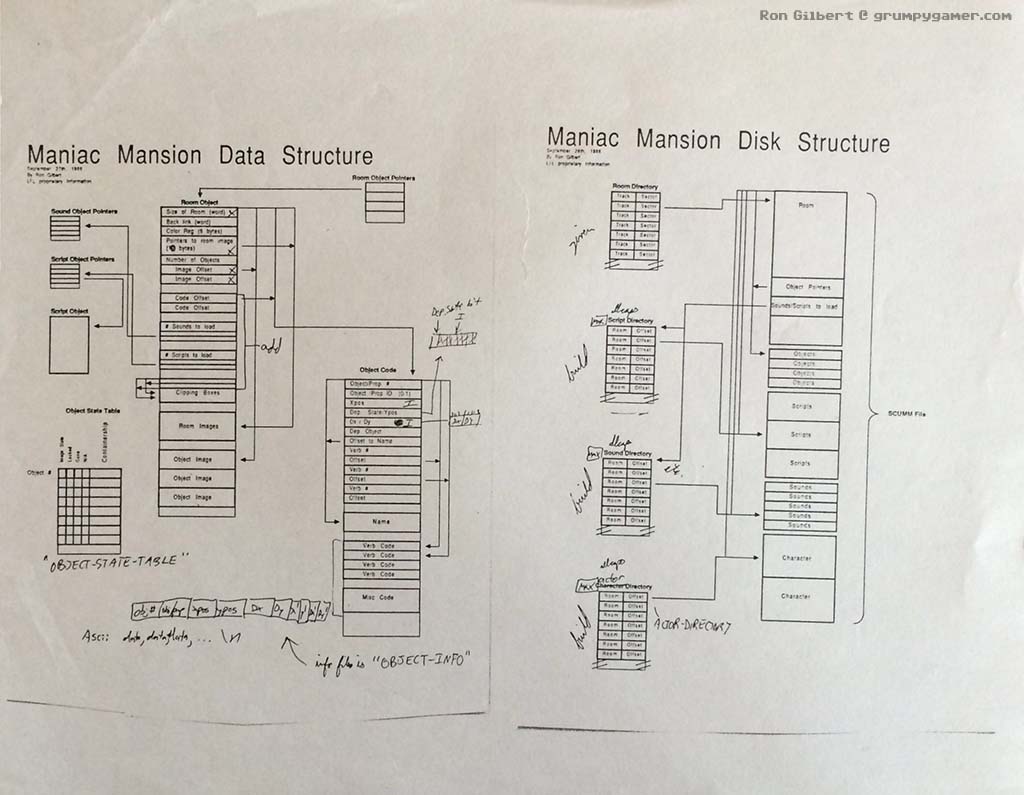

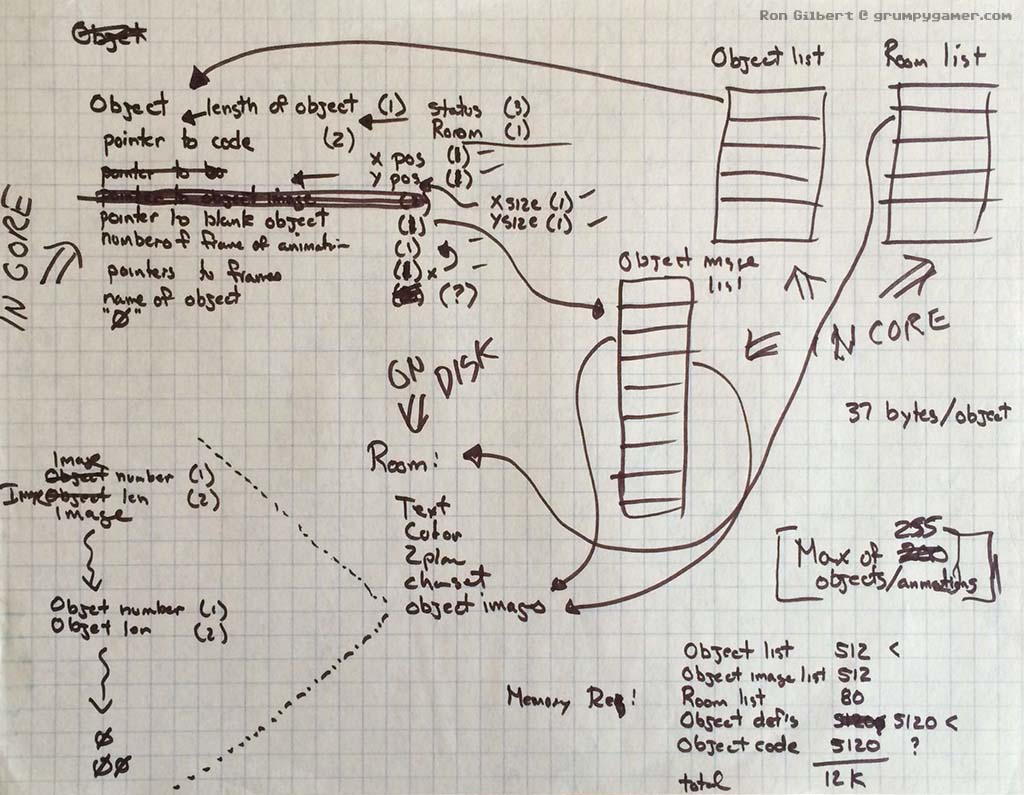

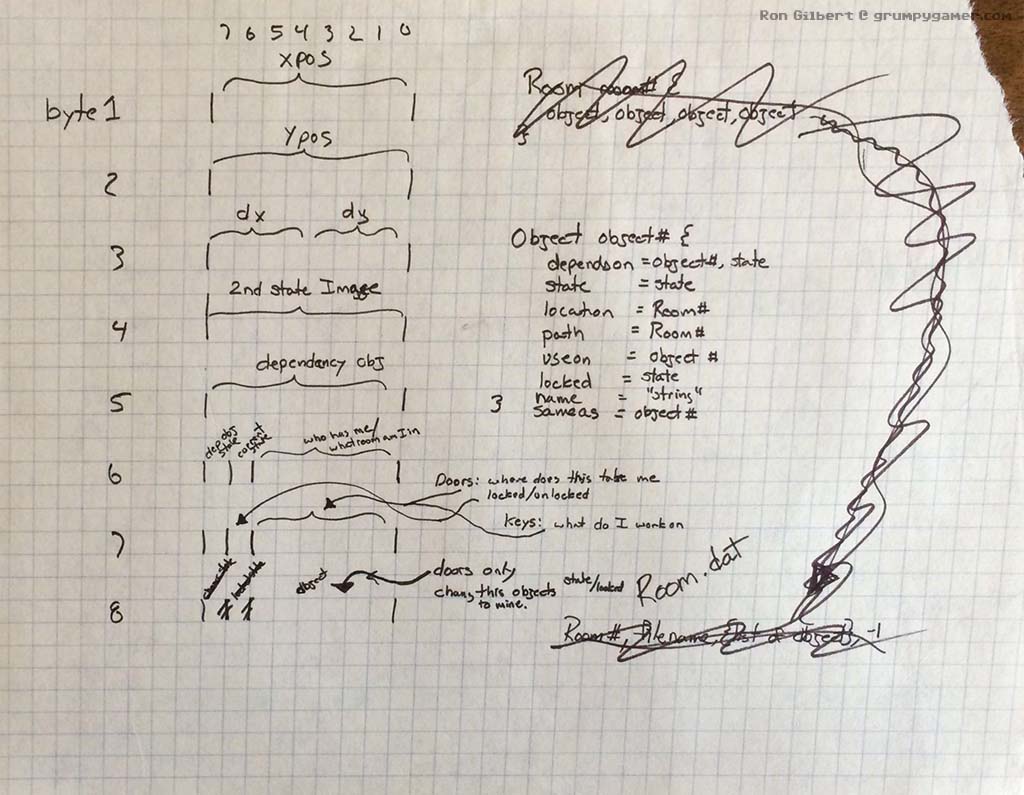

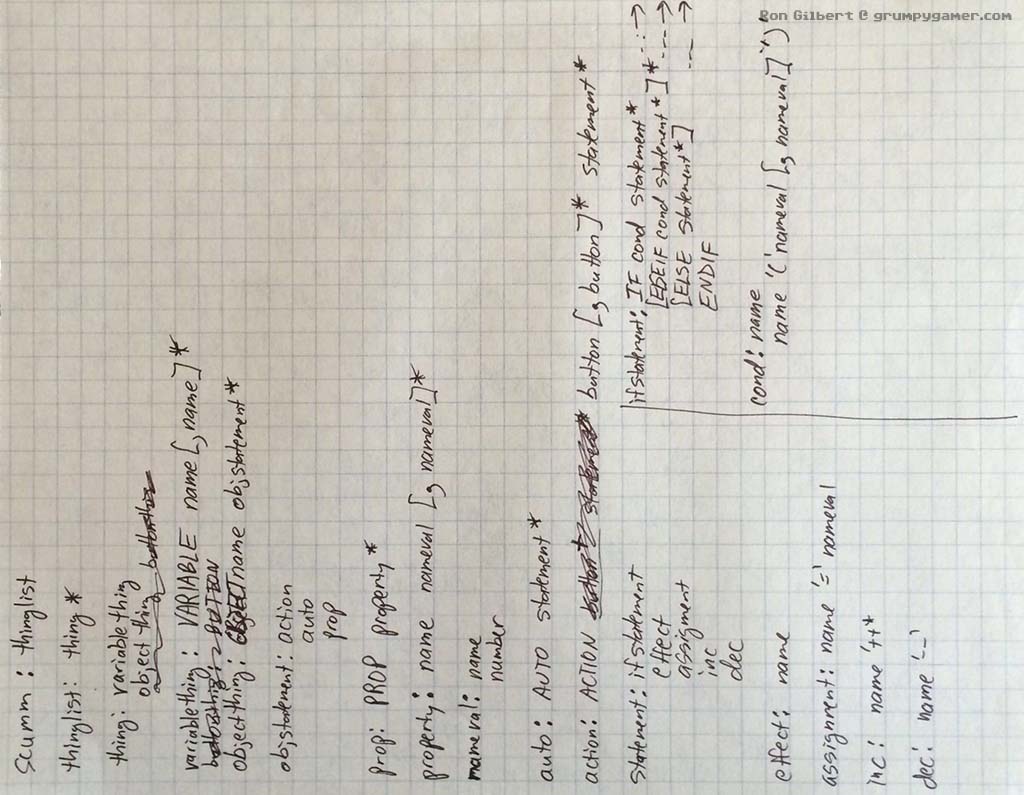

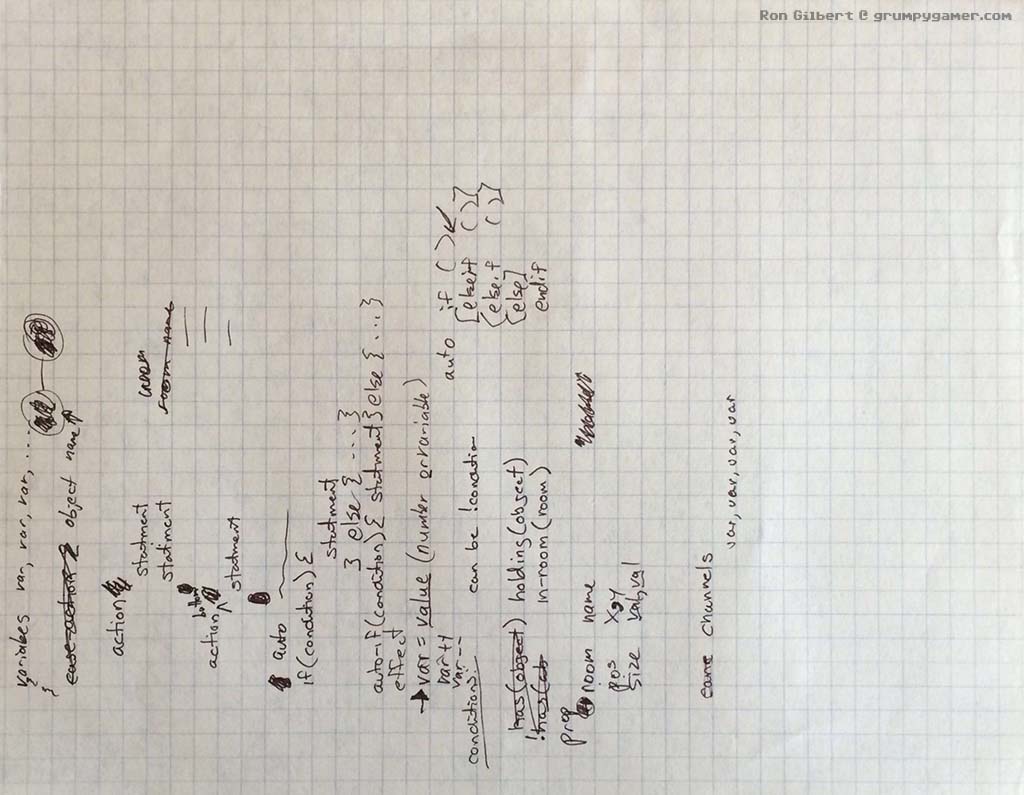

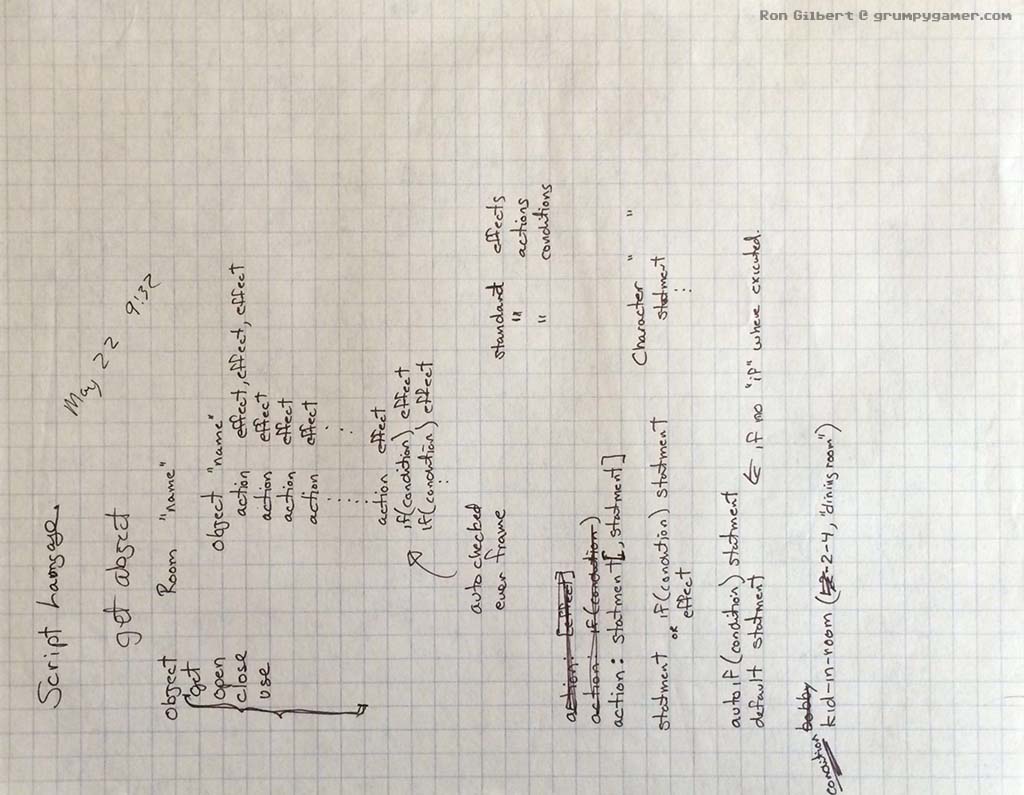

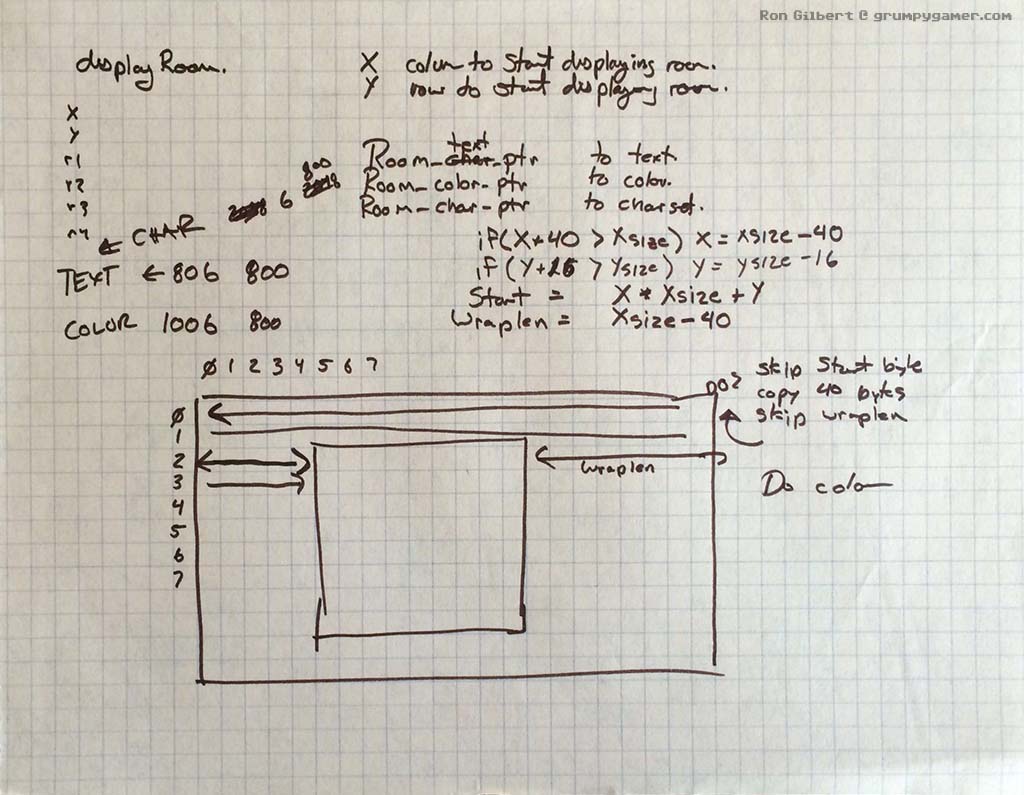

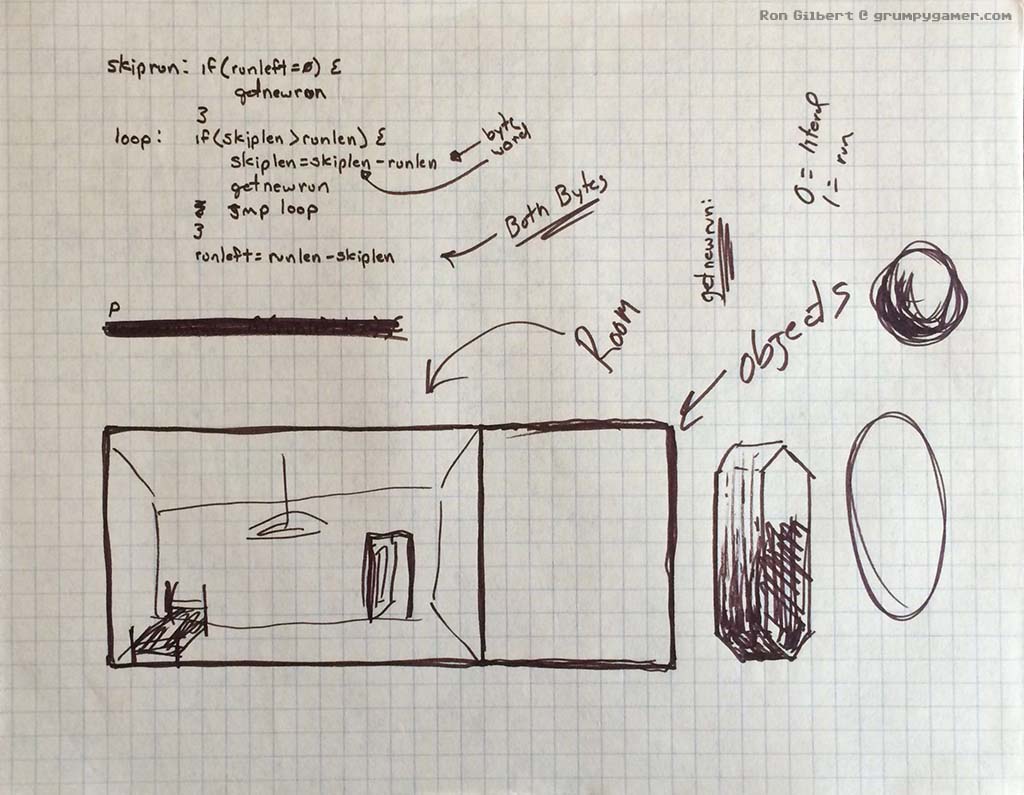

More crap that is quickly becoming a fire hazard. Some of my notes from building SCUMM on the C64 for Maniac Mansion.

I’m not sure who’s phone number that is on the last page. I’m afraid to call it.

I’m looking for some good recommendations on modern 2D point-and-click adventure game engines. These should be complete engines, not just advice to use Lua or Pascal (it’s making a comeback). I want to look at the whole engine, not just the scripting language. PC based is required. Mobile is a ok. HTML5 is not necessary. Screw JavaScript. Screw Lua too, but not as hard as JavaScript.

I’m not so much interested in using them, as I’d just like to dissect and deconstruct what the state of the art is today.

P.S. I don’t know why I hate Lua so much. I haven’t really used it other than hacking WoW UI mods, but there is something about the syntax that makes it feel like fingernails on a chalkboard.

P.P.S It’s wonderful that “modern 2d point-and-click” isn’t an oxymoron anymore.

P.P.P.S Big bonus points if you’ve actually used the engine. I do know how to use Google.

P.P.P.P.S I want engines that are made for adventure games, not general purpose game engines.