The Cave will be out on the 22nd on PSN and Wii U and the 23rd for XBLA and PC on Steam. It’s also coming out on the Mac and Linux! They should just change the name of the month to Cavuary.

It’s always hard to write your own about pages. I should have my mom do it, she always has nice things to say about me.

I started making games because I loved to program and I loved to tell stories and the two seemed to intersected nicely.

I wrote a program for the Commodore 64 (greatest computer ever made) called GraphicsBASIC that extended the rather boring built-in Basic that includes commands to gain access to the graphics and sound.

In 1985 I got a job working at Lucasfilm Games (now called LucasArts) porting Koronis Rift and Ballblazer from the Atari 400/800 to the Commodore 64.

In 1986 Gary Winnick and I created and designed Maniac Mansion.

During its production, I developed the SCUMM System (Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion).

I co-designed the Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade adventure game with Noah Falstein and David Fox.

I am also the creator and designer of The Secret of Monkey Island and Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge. A game about a pirate.

I am the co-founder of Humongous Entertainment where we made some amazing adventure games for kids like Putt-Putt, Freddi Fish and Pajama Sam.

I was the producer of Total Annihilation.

I co-created DeathSpank with Clayton Kauzlaric and was the designer of the first two DeathSpank games.

I worked at Double Fine for a bit making a game I’ve had rolling around in my head for close to 25 years called The Cave. Double Fine was sold to Microsoft, who now owns The Cave, and once again I got nothing and someone else owns my IP. FU TS.

I released Scurvy Scallywags in The Voyage to Discover the Ultimate Sea Shanty: A Musical Match-3 Pirate RPG (or SSITVTDTUSS:AMMTPRPG for short) for iOS and Android.

I finished a new point & click adventure game called Thimbleweed Park and the completely free Delores.

I then went and made Return to Monkey Island in total secret.

Now I’m working on an action game Rogue-like-lite called Death By Scrolling released for PC in Q4 2025. Consoles coming Q1 2026.

If you missed the carnival this summer, all is not lost…

I knew The Twins were going to be trouble. I should have cut them.

Sometimes it feels like Clayton Kauzlaric and I have a game-making addiction problem. We both have day jobs where we sit around all day long and make games for money, but then we go home and make games for free. If God didn’t want us to make games he shouldn’t have made it so much damn fun.

Over the past few years we’ve made around ten iOS games in our spare time. We’d work on one for a month and then some new idea would hit us and we’re on to that. ADD game designers. The Big Big Castle! is the second one we’ve actually gotten around to finishing. The first was a word game called Word Spiral. Both are for the iPad.

The Big Big Castle! stared out because I wanted to play around with Box2D, then Clayton brought up this idea he’s had for the last 10 years about building stuff and watching it fall down, so we started working on that. Clayton’s nine year old son said he’d like to blow up the castles he’d just built, so we added that, then we thought it would be fun if you could destroy castles your friends had built, so we added that.

The Big Big Castle! is the result of a few months of spare time on the weekends. It’s just a fun little game. A labor of love we thought we’d share.

It’s FREE so what have you got to lose. If you feel guilty about pirating Maniac Mansion, Monkey Island, DeathSpank or Putt-Putt Saves the Zoo, buy a coin pack and we’ll call it even.

I watched The Color of Money last night. Two things struck me about the film: 1) Holy crap is Tom Cruise young and 2) I really wish Paul Newman wasn’t dead.

I’m embarrassed to say I didn’t know Martin Scorsese directed it. He’s one of my all-time favorite directors and I keep thinking I’ve seen every movie he’s done, and then some movie pops up with his name on it.

The reason I watched The Color of Money was I had just seen The Hustler.

The scene with “Fast” Eddie playing Fats is simply amazing. It’s goes on and on and you’re feeling the exhaustion Eddie must feel. Then Jackie Gleason gets up, goes into the restroom, freshens up, puts his coat back on and comes out for more. A new man. My heart sank with Eddie’s.

It’s hard to imagine a scene that long in a modern film. Movie audiences need things to go go go. It feels like we’ve lost the ability to sit back and enjoy something that slowly unfolds. Really slowly unfolds. Sometimes that’s important. A few quick cuts and we could have been told “Fast” Eddie was tried, but we needed to feel it with him.

People said Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy was a slow movie in the mold of 70’s thrillers. True, it was slow by today’s standards, but still felt like it moved along. Try going back and watching The French Connection. That’s a slow movie, but it doesn’t suffer one bit as a result.

Adventure games are slow affairs. I worry few modern gamers have the patience for them anymore. Today, if someone spends more than 5 minutes trying to figure a puzzle out, they wonder where the pop-up hint is? They become anxious. Go go go. Good puzzles are meant to be chewed on for a while. Thought about. Mulled over. Put aside. Then spontaneously come rushing back as our subconscious figures it out.

A good adventure puzzle never leaves you wondering what to do, only how to do it.

Rock, Paper Shotgun

Eurogamer

The Verge

Kotaku

Giant Bomb

International House of Mojo

Ars Technica

Joystiq (No, I didn’t do all the programming, that was done by the much-better-than-I-am Double Fine programmers)

PC World

Pig Mag

Destructoid

Der Standard

Inside Gaming Daily

XBIGY Games

GameZebo

SEGA Portal

Gamers Global

Gaming Blend

Inside Gaming Daily

Let me know if I’ve missed any.

My father passed away in Feb 2012. He suffered a massive stroke a year and a half before and after a few months of optimism on our part, he started a slow and fateful decline, so his passing was not unexpected.

This is how I will always remember my relationship with my dad.

The two of us sitting around doing something nerdy involving computers or electronics. He taught me to program and fueled that passion as often as he could. We owned a home computer before the Apple II existed and even before most people knew a computer could fit in someone’s house.

He had a Ph.D in Astrophysics and it’s hard to describe how wonderful it was growing up with a father who could answer absolutely any question I had about spaceships, rockets, planets, stars, galaxies, quasars, black holes, asteroids, the sun or the moon. I could point into the night sky and ask “what’s that?” and he could tell me after only a moment’s hesitation.

I am who I am today because of him. Maniac Mansion, Monkey Island, Putt-Putt or Pajama Sam would not exist if not for him and the way he taught me to think and devour learning new things. He taught me to love to read, appreciate art and to always question my own beliefs and to be curious and inquisitiveness.

I’m sad he is gone and will miss him terribly, but I will forever be grateful for what he left me. Our life on this earth is not only what we did, but what we left behind for others.

David Gilbert

Scientist

Avid fisherman (ok, never understood this one)

Ham operator (ke7gi)

Best. Dad. Ever.

1939 - 2012

Well, I think it’s “time” to “leak” some more concept “art” for the amazing game I’ve been working on at Double Fine for the past 9 months.

After posting the previous concept art of The Scientist and The Mobster, I started reading all the adventure game forums and other gaming sites and I noticed a common reaction along the lines of “Hey Ron, those are great and all, but what we really want to know is if the game will have an old carnival ticket booth and a ceiling mounted laser cannon!”

Well, I’m happy to officially confirm that the game has both an old carnival ticket booth and a ceiling mounted laser cannon in it. I don’t want to reveal any spoilers, but one of them is going to hurt like hell.

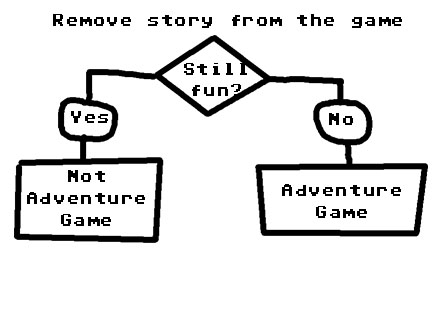

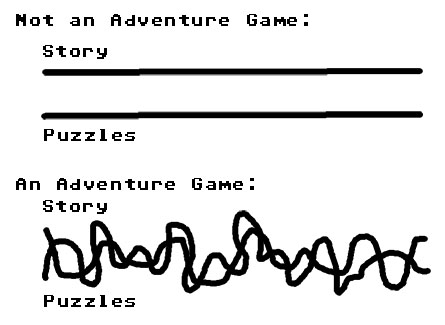

What makes an Adventure Game an Adventure Game?

Is Limbo an Adventure Game or just a puzzle game? Some people called L.A. Noir an Adventure Game but it lacks some of the basic components of an Adventure Game. Or does it?

Why do we call them Adventure Games? If you faithfully made Monkey Island into a movie, I doubt it would be called an Adventure Movie or even an Action/Adventure Movie.

I guess we call Adventure Games Adventure Games because the first one was call Adventure. I see no other reason they are called Adventure Games.

Semantics aside, what makes an Adventure Game an Adventure Game?

Inventory? Pointing? Clicking? Story? Low Sales?

Certainly not Adventuring.